Learn Multi platform PDP11 Assembly

Programming... With Octal!

|

Don't like to read? you can learn while you

watch and listen instead!

Every Lesson in this series has a matching YOUTUBE video... with

commentary and practical examples

Visit the authors Youtube

channel, or Click the icons to the right when you see them

to watch the Lessons video! |

|

Before the ZX Spectrum, the CPC and

Nintendo, computing was literally a 'bigger' thing... the PDP-11

by DEC was an early computer...

Impressively advanced for it's time, it's programming language

resembles the 68000, and some of it's other design ideas can be

seen in other processors today.

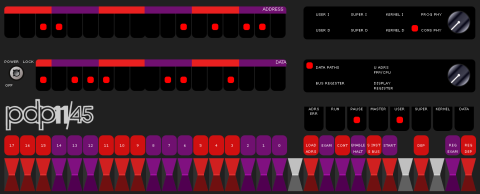

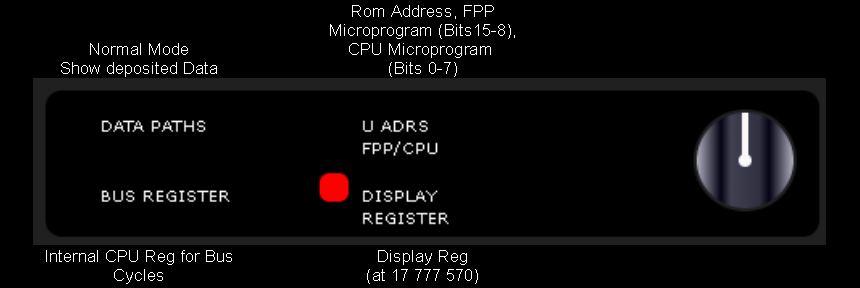

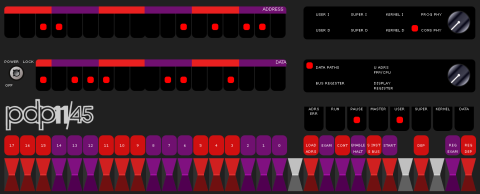

The front of the PDP unit is lit up with LED's and covered in

switches... these aren't just a sci-fi prop though, the PDP panel

can be used as a hardware monitor and debugger, allowing any

address in the CPU's memory to be read and altered.... in fact

booting the PDP-11 may require setting many of these switches to

program a 'boot sequence' into ram.

|

A PDP/40

The PDP-11 front panel. |

Useful Resources:

ChibiAkumas Tutorials

PDP-11 Simple Samples

PDP-11 Multiplatform Specific Lessons

PDP-11 Platform Specific Lessons

PDP-11 SuckShoot Series

What is the PDP and what

the heck is 'Octal'?

The PDP-11 is an 16-Bit processor - in the 1970s it was classed as

a 'MiniComputer'... the CPU unit was around the size of a

microwave, and when connected to disk drives and other hardware,

the whole computer was the size of a single 'rack'

Octal is a numbering system known

as 'Base-8' - it uses digits 0-7, effectively grouping digits

from sets of 3 bits.

Octal allows binary to converted to

digits, without using any extra 'letters', allowing for easier

display and usage on conventional hardware like calculators.

If we're going to use the PDP-11 we

need to get used to octal, as that's how all the documentation

is written... fortunately, because it only uses 'digits' it

won't be too strange, and we can mostly not worry about it!

While Octal is the 'norm' in PDP,

Our Assembler can use other formats with the following syntax.

Base

|

Symbol

|

Alternate |

Example

|

Radix command |

| Binary |

^b

|

|

#^b101 |

.RADIX 2 |

| Octal |

(default)

|

^o |

#777 |

.RADIX 8 |

| Decimal |

.

|

^d |

#987. |

.RADIX 10 |

| Hexadecimal |

^x0

|

|

#^x0FF |

.RADIX 16 |

| Ascii |

'

|

|

#'A |

|

^FF seems to work for HEX as well.

the PDP 11 is a Little

Endian system... Low bytes are stored at even numbered

addresses, and High bytes are stored at odd addresses

|

| Oct |

Dec |

Hex |

Binary |

| 1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 2 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

| 3 |

3 |

3 |

11 |

| 4 |

4 |

4 |

100 |

| 5 |

5 |

5 |

101 |

| 6 |

6 |

6 |

110 |

| 7 |

7 |

7 |

111 |

| 10 |

8 |

8 |

1000 |

| 11 |

9 |

9 |

1001 |

| 12 |

10 |

A |

1010 |

| 13 |

11 |

B |

1011 |

| 14 |

12 |

C |

1100 |

| 15 |

13 |

D |

1101 |

| 16 |

14 |

E |

1110 |

| 17 |

15 |

F |

1111 |

| 20 |

16 |

10 |

10000 |

| 100 |

64 |

40 |

1000000 |

|

The PDP-11 and

UKNC content on this site wouldn't have been possible without the

help of 'aberrant'... who's also working on a UKNC port of

Chibiakumas!... not only is it an impressive feat, but the code is

incredibly well commented, and worth looking at for UKNC insights

You can check out aberrant's work here!

|

|

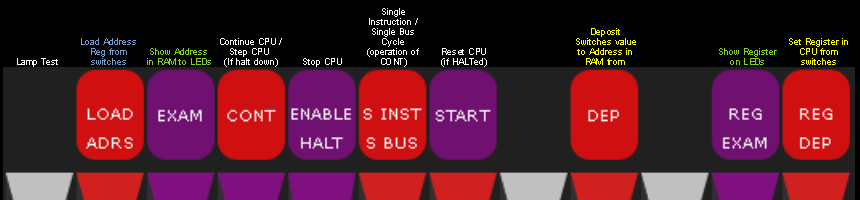

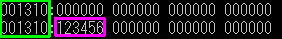

Using The PDP-11 Front panel

The PDP 11 has an advanced front panel, which effectively can

operate as a debugger, and is also able to program words of data

into memory... The

There are 18-22 SWITCHes numbered

0-17/21 - these are used to set a value to be used as an address

or as a value to store. the ADDRESS leds show the address being

set or probed, the DATA leds show the value at an

address/register

You can try out the PDP interface online... Here! |

|

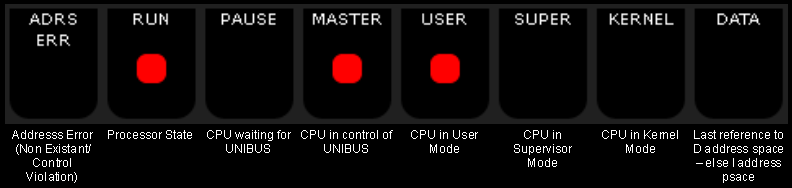

The other switches and leds have the

following functions:

The PDP-11's registers are ALL 16 bit.

Register

|

Details

|

Notes

|

R0

|

|

|

R1

|

|

|

R2

|

|

|

R3

|

|

|

R4

|

|

|

R5

|

LK |

Often Used to remember the return address during calls |

SP (R6)

|

SP |

Stack pointer |

PC (R7)

|

PC |

Used to remember running address |

If an Even register number (R0,R2,R4) is used for certain commands

(for example MUL)- the register and it's following will be used as

a 32 bit pair when the result is returned

|

|

Flags: -------- PPPTNZVC

|

Name |

Meaning |

| - |

unused |

|

| P |

Priority |

|

| T |

Trap |

|

| N |

Negative |

1=Negative |

| Z |

Zero |

1=Result Zero |

| V |

Overflow |

|

| C |

Carry |

1=Carry |

Unlike many CPUs, the flags on the PDP-11 are not stored in a

register, but are stored at memory address 777776-7 (in octal). |

The PDP-11 Addressing Modes

The PDP-11 has 8 different addressing modes... many are similar to much

later systems... in addition it has 4 'effective modes' which are defined

by using Reg 7 as a parameter

'Deferred' addressing is known as indirect

addressing on other systems

| Octal Representation |

Mode |

Description |

|

Sample Command |

68000

Equivalent |

effective result |

0 R

|

Register |

Value is taken from Registers itself |

Rn |

|

|

R |

1 R

|

Register Deferred |

Value is taken from address in register |

(Rn) or @Rn |

|

(Rn) |

|

2 R

|

Auto Increment |

Value is taken from address in register.... register increased

by bytes read |

(Rn)+ |

|

|

(Rn+) |

3 R

|

Auto Increment Deferred |

Value is taken from address at address in register.... register

increased by 2 |

@(Rn)+ |

|

|

((Rn+)) |

4 R

|

Auto Decrement |

Value is taken from address in register.... register decreased

by bytes read |

-(Rn) |

|

|

|

5 R

|

Auto Decrement Deferred |

Value is taken from address at address in register.... register

decreased by 2 |

@-(Rn) |

|

|

|

6 R

|

Indexed |

Value is taken from address in register + a fixed number |

n(Rn) |

|

(2,R2) |

(Rn+n) |

7 R

|

Indexed Deferred |

Value is taken from address at address in register + a fixed

number |

@n(Rn) |

|

|

((Rn+n)) |

2 7

|

Immediate |

Fixed numeric value |

#n |

|

#n |

|

3 7

|

Absolute |

Value from fixed address |

@#A |

|

A |

|

6 7

|

Relative |

Value from relative address |

A |

|

|

|

7 7

|

Relative deferred |

Value from address in address |

@A |

|

|

|

MACRO-11

Macro-11 is the Assembler that is used by RT-11... Macro-11 is case

insensitive, it also only uses the first 6 characters of labels and

symbols... this limit extends to file names -which must be 6 characters or

less... eg 123456.MAC or ABCDEF.asm

We can complement (flip the bits) of a constant with ^C eg #^C123

Missing commands

| AND |

We don't have an AND command, but we can fake one, we flip all

the bits of our register, and use BIS (OR)

Here is the equivalent of AND #7 |

bic #177770,r0 ;effecitive AND #7

or

com R0 ;flip bits

bic r0,r1 ;clear |

CALL

RETURN |

We need to specify a register to use with calls

|

JSR PC,\addr

RTS PC

|

PUSH reg

POP reg |

Use AutoInc and AutoDec

|

MOV \reg,-(SP)

MOV (SP)+,\reg

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lesson

1 - Getting started with PDP-11!

For our PDP-11 development we'll be using R11 as an

assembler , and "UKNC back to life" as an emulator...

The UKNC is PDP-11 compatible (we can also run the tests on R11

itself)

There's a video of this lesson, just click the icon to

the right to watch it -> |

|

|

|

|

Character Limits: The joy of 6!

MACRO-11 is limited in many places to 6

characters... this is especially true in filenames... for labels and

symbols we can use more letters, but only the first 6

will be used - the rest will be ignored.

You will notice we do use longer labels in many

cases in these tutorials - this is to give the functions easy to

understand names.

Please bear in mind that the assembler we're using only processes

the first 6 |

|

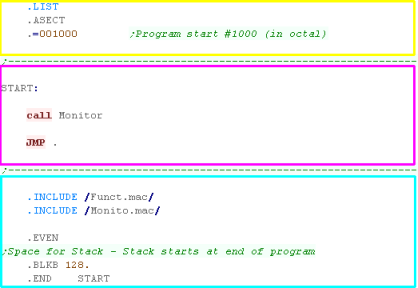

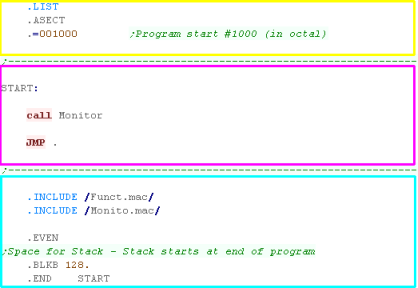

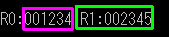

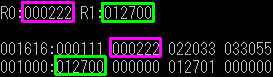

Structure of an ASM (.MAC) source

file

Lets look at a simple file (Min.MAC)

we have a header - Our program is defined

to start at #1000 in octal

In our body we're running a simple monitor

program - this is where you would put your code

In our footer we're including some useful

files (with a .INCLUDE statement), we're then defining a block of

128 bytes - this is for the stack, which will default to the top

of our program area on R11

MACRO-11 files often have the extension .MAC rather than .asm |

|

|

Notice the

JMP . (full stop)? - A full stop in Macro-11 is the same as * in

other systems, it returns the current line address..

So Jmp . is effectively an infinite loop.

|

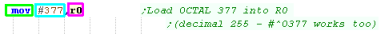

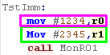

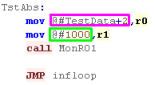

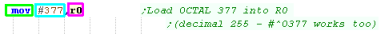

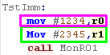

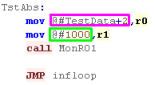

Loading Values

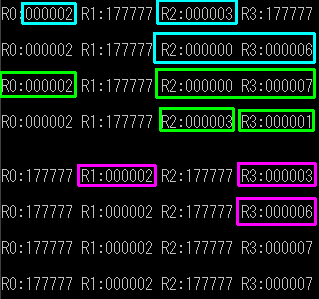

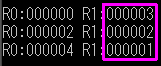

WE have 6 general purpose (R0-5)registers we can use for

whatever we want,

Lets look at the MOV command - it move a

value into a register

When we set a register, our source is on the

left, and the destination is on the right

This is a 16 bit command, the value will be two bytes, and by

default the number will be in OCTAL - #377 in octal is 255 in

decimal |

|

| The register will be loaded with the value |

|

By default we're specifying Octal, but we can specify other

values...

We can specify Decimal by putting a . at

the end of the number (or ^d at the start)

We can use Hex by putting ^x at the start

we can use ascii by putting ^' at the

start (we don't need the second ')

By default we're set to Octal (Base 8 / Radix 8) but we can force

octal with ^o

All the previous examples loaded a 16 bit value, but we can load

an 8 bit value by putting a B at the end of

MOV... the byte will be sign extended to a word (bit 7 will fill

bits 8-15 |

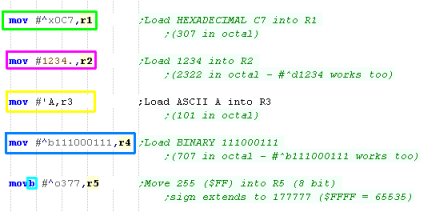

|

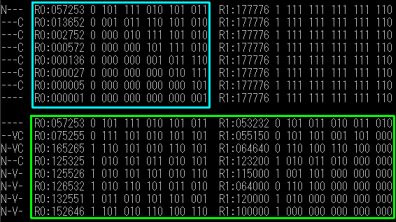

| Here are the results! - note B5 was sign

extended, filling all the unused bits with 1's |

|

By default

PDP-11 works in 16 bit, but many commands can have B tagged on

to the end to work in bytes...

Check out the cheatsheet to see all the details of the commands.

|

|

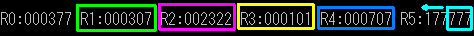

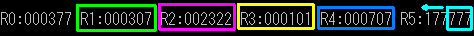

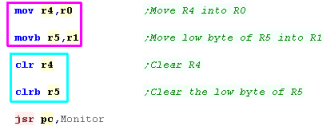

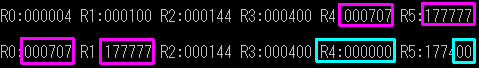

If we don't want to default to octal when we specify a # number,

we can do so with the .RADIX command

This changes the base as we require, we can always override the

base with the ^ commands we already looked at.

We can use Binary, Octal,

Decimal or Hexadecimal

Although it's tempting to default to HEX or DEC - we'll stick with

OCTAL in these tutorials - as it's how the systems was designed. |

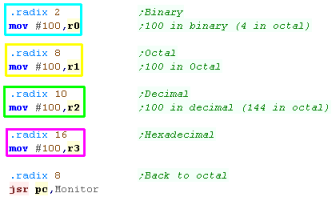

|

| here is the result |

|

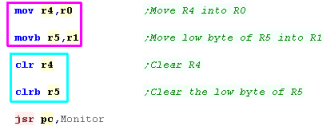

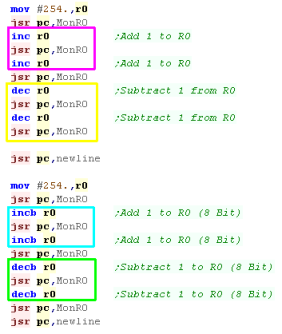

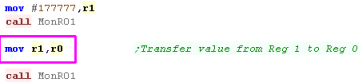

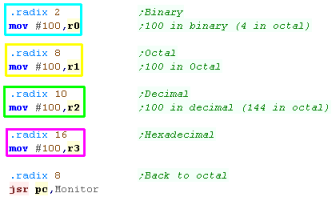

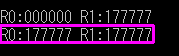

We'e looked at moving 'immediate' values (numbers with a # in

the command) - but we can also transfer values

from one register to another

We can also load zero with the CLR (clear)

command - this uses less memory than MOV #0,r4 |

|

| Here are the results |

|

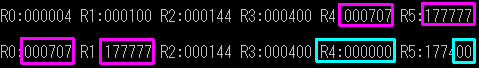

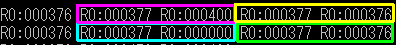

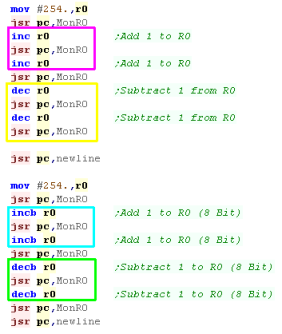

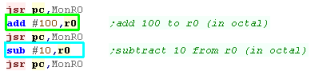

INC and DEC

Just like the CLR command can quickly set a register to Zero -

we'll frequently want to take a register and add 1 or subtract 1

We'll need this for loop counters, reading data, and plotting

pixels to a screen... well we have special commands to do this INC

and DEC

by default INC and DEC

are 16 bit, but as before we can use INCB and

DECB |

|

When we did the INC the word value up by two... when we did the

DEC it reduced again...

When we did INCB - the Byte went up, but when it went over #^o377

(Decimal 255) it rolled back to zero because 255 is the limit of

the byte... the DECB commands had the expected effect |

|

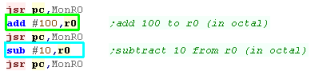

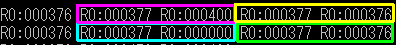

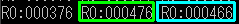

ADD and SUB

Of course,we can ADD and SUBtract other values!

We just specify the ADD/SUB with two parameters , the immediate

value or register on the left , and the destnation register on the

right |

|

| Here are the result |

|

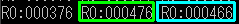

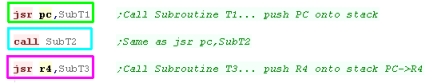

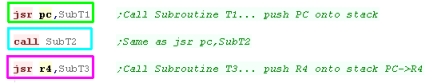

JSR and CALL / RTS and RETURN

The JSR and RTS functions on PDP-11 perform CALLS (Jump To

Subroutine) and RETURNs (Return from Subroutine)

Each function takes a register - JSR pushes the register onto the

stack , then puts the program counter in that register... RTS pops

the register off the stack, and moves it to the program counter..

.

Generally we'll just want to use JSR PC,{label}

and RTS PC.... but rather than typing PC every time, we can

use CALL {label} and RETURN {LABEL} - these

are shortcuts supported by the assembler.

However... we can use a different register! If we use

JSR R4,{label} and RTS R4 - then R4 will get the calling

address... handy for getting values in .BYTEs following the CALL -

or just getting the running address. |

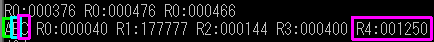

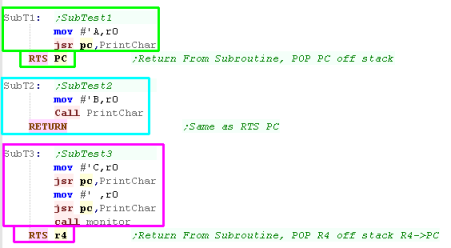

|

| here are the results... not R4 took the

PC of the calling address |

|

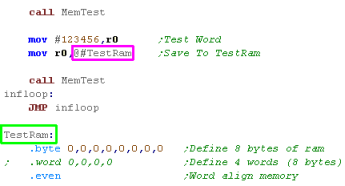

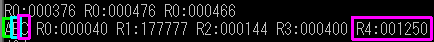

Not just Registers!

We've looked at registers and immediates - but of course PDP can

do far more!

Lets take a look at Writing to ram!

We can write to an address by using a label and putting a @ in front

of it. |

|

The value was saved to Ram...

There's lots more of options for saving and loading... but we'll

leave them until next time! |

|

|

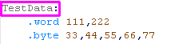

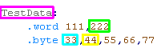

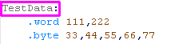

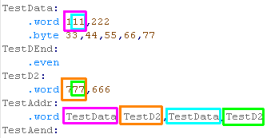

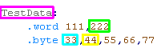

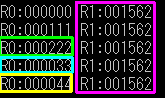

We can define BYTEs and WORDs in our code for

our reading or writing... but PDP-11 is 16 bit and needs to be

WORD aligned - we should put an .EVEN command after the data.

|

Lesson

2 - Addressing modes

We looked at the basics of PDP last time, but it's time to

start getting serious!

Although it's relatively old, PDP-11 has a

huge number of addressing modes... and now it's time to learn

about all of them. |

|

|

|

|

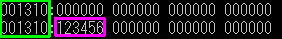

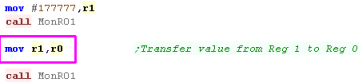

0R - Register

Register addressing is something we've already looked at... its

where we're transferring data between registers!

In this example, we transfer the value in R1

into R0

We just specify the register name R0-R5.... Note: R6 is called SP,

and R7 is PC |

|

| We transferred R1 to R0 |

|

Wondering what 0R and 1R Mean?

We'll these are the octal representation in the bytecode..R would

be a register number - and this code would be used in the source

or destination field to specify the

value source...

You don't actually need to know these for programming - but we'll

include them here for completeness |

|

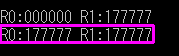

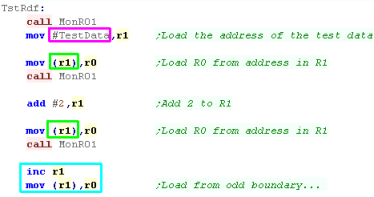

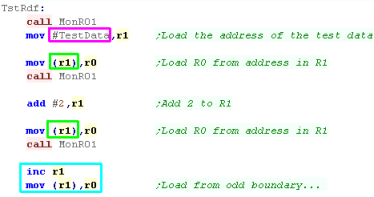

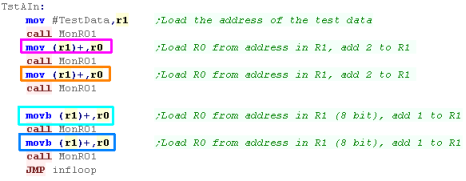

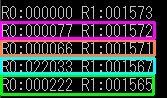

1R - Register Deferred

Register deferred sounds

confusing, but it doesn't need to be!... this would be called

'Indirect register addressing' on other systems....

Basically, we're going to read from an address - and that

address is held in a register... to do this

we put the register in bracket.

Notice that whether we read a word from an odd boundary or even

one, we get the same result!... this is

because the PDP-11 requires the word data to be aligned on even

boundaries.

Low bytes are stored at even numbered addresses, and High bytes

are stored at odd addresses So we get the same value as last

time,even though address is +1 |

|

| The values are read in from the address in R1 into R0 |

|

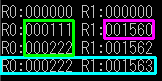

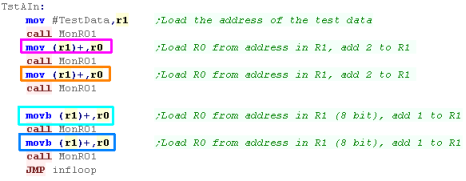

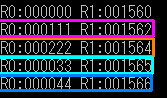

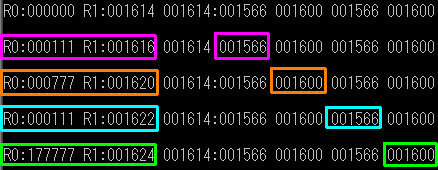

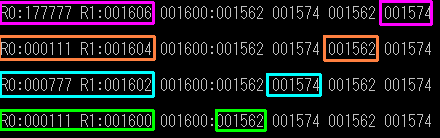

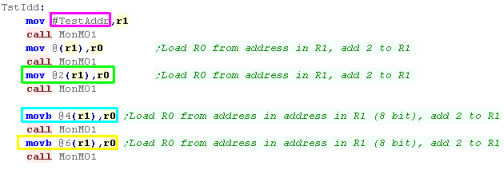

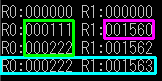

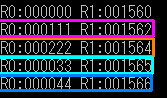

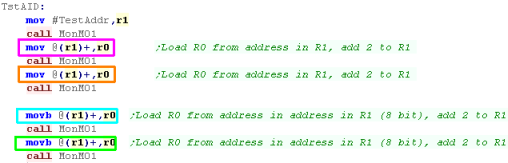

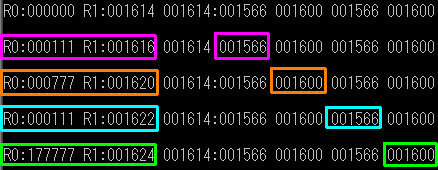

2R - Auto Increment

We read from a register's address last time... we can also get

that address to increment after each read...

We can use a Register as a source address - and sequentially read

from consecutive memory addresses (for example if we're processing

a bitmap file, or a text string)

We just put the register in brackets () and

and add a + to the end... this is because the value in the

register goes up AFTER the read

If we're reading in words, the address will increase by 2 - if

We're reading in bytes, the address will increase by 1

MOV (SP)+,Rn is effectively our POP command |

|

| Here are the results |

|

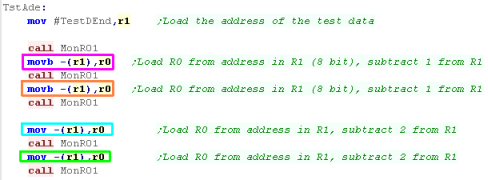

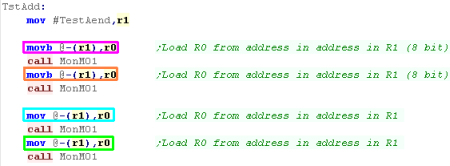

3R - Auto Increment Deferred

This is a combination of the

last two - we'll read from the address in the address in a

register - then increment the register by 2

Effectively the register should point to an entry in a vector

table (a table of address pointers)

We specify this addressing mode by using @(Rn)+

|

|

Here are the results

|

|

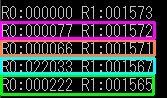

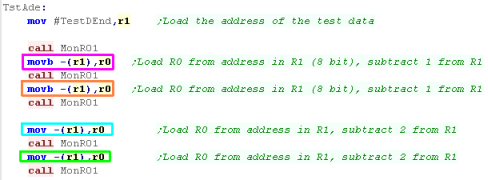

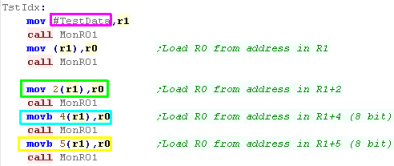

4R - Auto Decrement

This is the opposite of "2R - Auto Increment"

We specify -(Rn) ... note this time the

decrement occurs BEFORE the read

MOV Rn,-(SP) effectively our PUSH command |

|

| Here are the results |

|

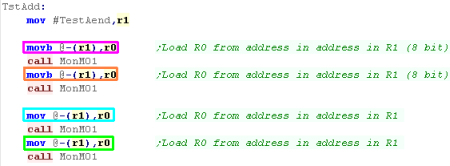

5R - Auto Decrement Deferred

This is the reverse of 3R -

we'll decrement the address by 2, and then we'll read from the

address in the address in that register

This is useful for reading from a list of pointers backwards...

We specify @-(Rn) to use Auto Decrement

Deferred mode |

|

Here are the results

|

|

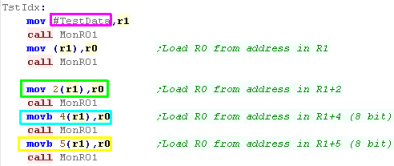

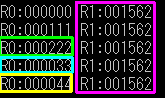

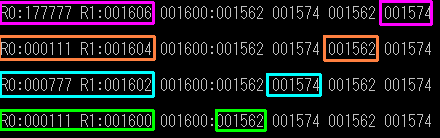

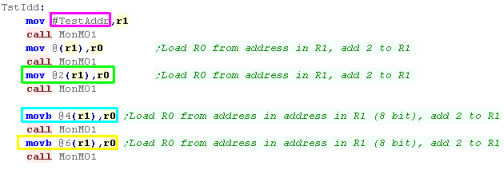

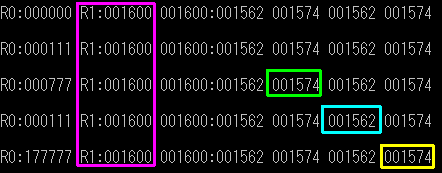

6R - Indexed

Indexed addressing takes the value from an address calculated

from a register PLUS an offset

This allows us to point a register to a bank of data (for a

player, or device driver for example), and give an offset for

read/write operations...

The format is v(Rn) - where v is a positive

or negative offset from the register.

|

|

| We've read in the values from the addresses |

|

7R - Indexed Deferred

Indexed Deferred is a combination of the last two... the address

in a register plus an offset is used as a source address in a

vector table - and that address is used as the source address for

the final value.

To specify this we use @v(Rn) where v s |

|

| Here are the results |

|

|

If the

register parameter is the program counter (R7 - PC) we have 4

extra 'effective' options...

We don't have to worry about this - The assembler handles this

for us as needed.

|

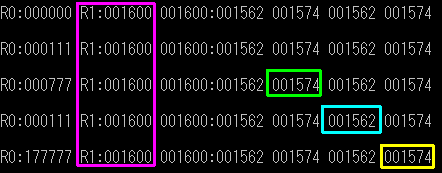

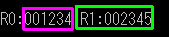

27 - Immediate

We've seen Immediate values many times, these are just values

specified in the line of the code...

They are specified with #number |

|

| here are the results |

|

37 - Absolute

Absolute addresses are where we're reading in from a fixed

memory location...

Normally we will probably use a label,

but we can also use a numeric address.

|

|

Here are the results

|

|

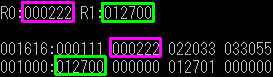

67 - Relative

Relative addressing is where

we are using a value read from memory relative to the Program

Counter (the current running code)

.

The program counter can be addressed with .

- this returns the current line of code. we can use this as part

of a relative calculation |

|

| Both calculations load from the same address |

|

During Execution in the processor the PC register

always points to the next command (the next word after the current

command).

the full stop (.) is the assembler directive, which represents the

address of the current command, so is 2 bytes before the Program

Counter. |

|

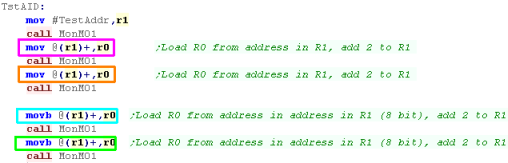

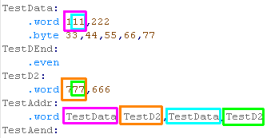

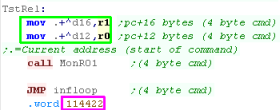

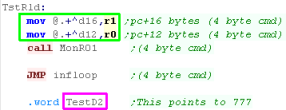

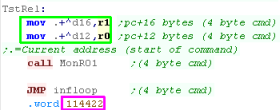

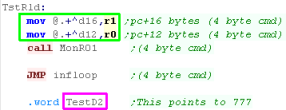

77 - Relative deferred

| Once again - Relative deferred uses an

offset from the program counter, but this time it loads the

address from the resulting address - and gets the value from that

address for the parameter |

|

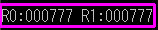

| The value at TestD2 (000777) was loaded

into both registers |

|

Lesson

3 - Conditions, branches and loops

We've looked at loading in fixed values, but we need to have

some way of controlling what happens depending on the values in

registers and memory...

This is where conditions come in!... lets learn all about them.

|

|

|

|

|

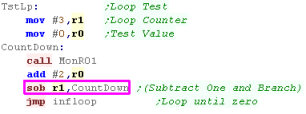

Looping with SOB!

on some systems looping can be a son of a bitch... but when we

need to do a loop with PDP, there's no need to cry* - the PDP

makes it easy with SOB! (Subtract One and Branch)

This will subtract 1 from the specified register, then loop back

to the specified label if the register isn't zero - we can use

this as our loop (like Z80 DJNZ)

In this example we add 2 to R0 each loop

*Excuse me for the terrible jokes.. i'm done now!... probably... |

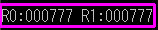

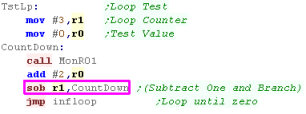

|

| The loop ran 3 times based on the count

in R1 - because it stops when it reaches zero, there was no 4th

iteration |

|

Fun with Flags.

As Branches are usually based on conditions, Before we look at

them, lets learn how to set and clear the flags - there are

special commands to do this!

Each flag has a 'set' command and a 'clear' command - we'll learn

what each flag means and how to use it in a moment.

Action

|

N |

Z |

V |

C |

All |

| Set |

SEN

|

SEZ

|

SEV

|

SEC

|

SCC

|

| Clear |

CLN |

CLZ |

CLV |

CLC |

CCC |

We're using a function called 'MonFlg' to show the flags, but it's

function is outside the scope of today's lesson

|

|

The flags will be set accordingly

|

|

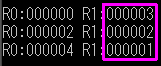

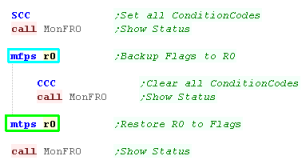

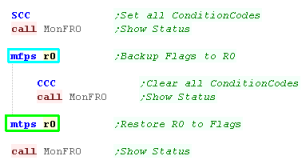

We can back up and restore the flags in one of our registers

with MFPS and MTPS

MFPS will back up the flags to a register

MTPS will restore the flags from the

register

It should be noted that these commands do not exist on many

earlier PDP-11 versions. |

|

| We backed up the flags into R0 ... zeroed

them and restored them from R0 |

|

You may think

that's a lot of 'set' and 'clear' commands - but that's just the

half of it!

You can actually 'create' commands with the correct combination

of bits to set or clear any combination of flags in one go! -

you'll need to see the byte data the command compiles to to

figure it out though - and it's probably not that useful!

|

|

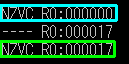

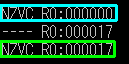

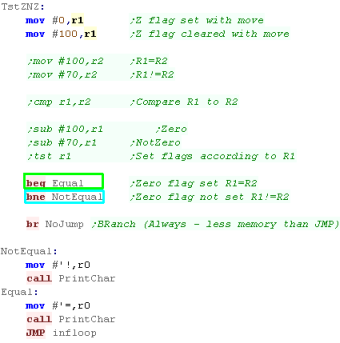

Zero flag (Z)... Equal / Not Equal

Whenever we do a MOVe, CoMPare, ADD or SUB the flags will be

set.

If the result is ZERO - Z will be true - otherwise it will be

false... Like many systems CMP sets the flags like a subtract

command, but doesn't change the registers.... so if the difference

is zero

BEQ will branch if Z is set (Branch if EQual

BNE will branch if Z is not set (Branch if

Not Equal)

There is a special branch... BR - this will ALWAYS branch!

Also notice the TST command - this will

update the flags according to a register - but does not change the

register itself. |

|

| The sample will show = if the result is Zero... or !=

if the result is not zero |

|

| BRanch and JMP

do the same thing in the sense that they always jump... but

BRanch takes fewer bytes - BR uses an offset in the 2 byte

command, whereas JMP uses an absolute address (total of 4

bytes)... but BRanch cannot 'jump' far away from the current

label (approx -256 to +255 bytes away) |

|

|

You'll notice lots of remmed out code -

this is other tests you can do to see how the flags are affected

- you really need to download the code and try it yourself,or

just watch the video!

|

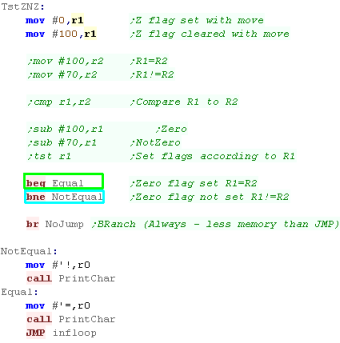

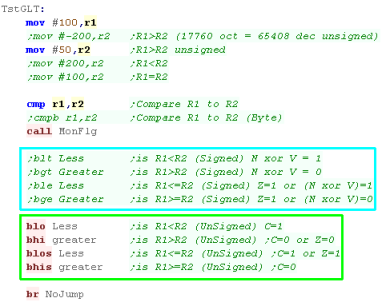

Unsigned - Carry (C), Negative (N)

and oVerflow (V)

Because of the way the CMP command works like a subtraction,

with unsigned numbers the Carry flag will be set

Signed numbers are a little more tricky, we'll have to consider

the oVerflow and Negative commands - fortunately the CPU handles

this for us, and gives us 4 commands for each

| Condition |

Signed |

Unsigned |

<

|

BLT

|

BLO

|

<=

|

BLE

|

BLOS

|

>=

|

BGE

|

BHIS

|

>

|

BGT

|

BHI

|

|

|

The flags will be shown, and a < or > will be displayed

onscreen

|

|

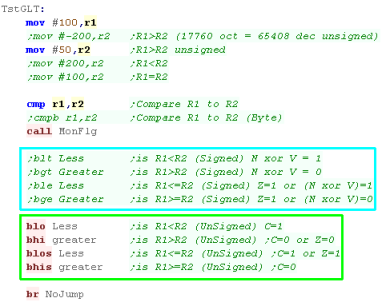

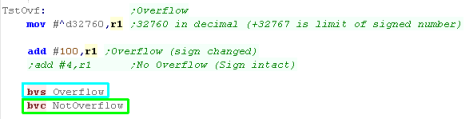

oVerflow (V) - those pesky signs!

Because when considering a signed number 32767 is 32767, but

32768 is -1... we have to be careful that adding a number, or

subtracting one won't cause the sign flag to unexpectedly

change... this is what the overflow flag (V) is for!

BVS will branch if overflow is set

BVC will branch if overflow is clear |

|

| O will be shown on Overflow... NO will be shown if there's No

Overflow |

|

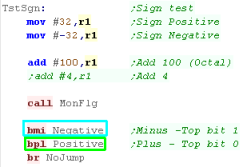

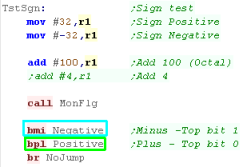

Negative (N) - Sign bit

The N flag will allow us to check a sign - it effectively takes

the value of the top bit of the result of the last operation.

BMI will branch if the value is negative

(minus - N set)

BPL will branch if the value is positive

(plus - N clear) |

|

| The flags and a + or - will be shown |

|

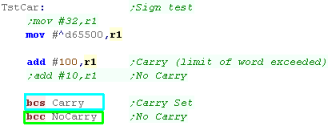

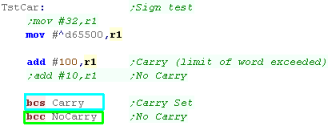

Carry flag (C)

When an addition or subtraction goes over the limit of a

register, or a bit shifting operation pushes a bit out the

register the Carry flag is set (it acts as a borrow with

subtraction)

BCS will Branch if Carry is Set

BCC will Branch if Carry is Clear |

|

| C will be shown if the Carry is set ... - will be shown if it

isn't |

|

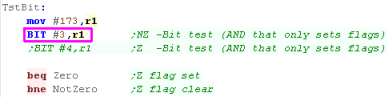

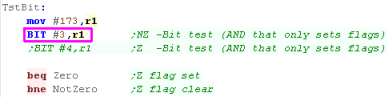

If we want to test one or more bits in a register we can do so

with the BIT command!

This is effectively an AND command - but it does not change the

registers - it will set the Zero flag depending on if the bits are

zero or not. |

|

| Z or NZ will be shown to the screen. |

|

Lesson

4 - Stack and More Maths

We looked at the AutoINC and AutoDEC addressing modes before

that effectively work as PUSH and POP - but we didn't explain

those!... lets look now at the stack and how JSR/CALL works

We'll also have a look at Multiplication and Division... and

using the Carry to combine two registers for 32 bit maths!

|

|

|

|

|

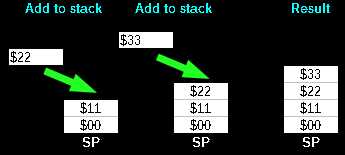

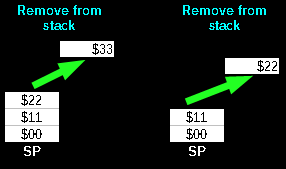

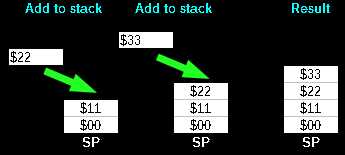

Stack Attack!

'Stacks' in assembly are like an

'In tray' for temporary storage...

Imagine we have an In-Tray... we can put items in it, but only

ever take the top item off... we can store lots of paper - but

have to take it off in the same order we put it on!... this is

what a stack does!

If we want to temporarily store a register - we can put it's value

on the top of the stack... but we have to take them off in the

same order...

The stack will appear in memory, and the stack pointer goes DOWN

with each push on the stack... so if it starts at $01FF and we

push 1 byte, it will point to $01FE

(This screenshot is from the 6502 - but the principle is the same

for the PDP-11) |

|

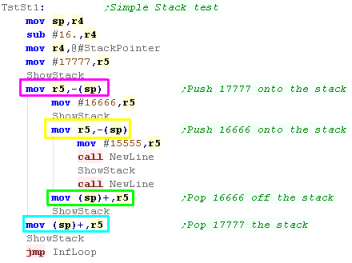

Macro-11 has MACROS!

In todays example we're going to define a MACRO!

This will create a 'command' that contains a series of other

commands - the assembler will replace any instance of 'ShowStack'

with the commands in the macro... |

|

|

This is just a simple example - Macro-11 also

supports parameters: .MACRO testmac param1,param2 would define

two parameters for the macro... these can then be used within

the macro.

For full info see the Macro-11 documentation

|

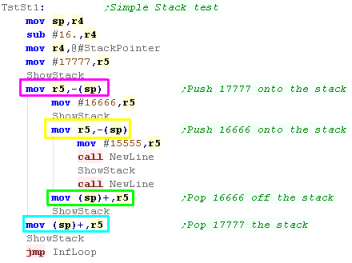

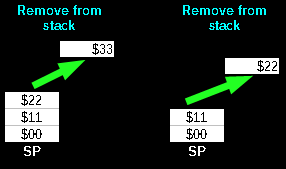

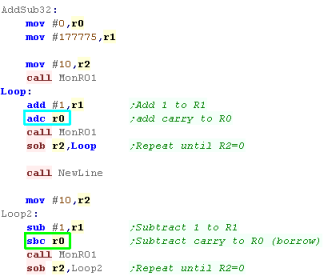

Using the Stack for

temporary storage

There will be many times we need to back up a register

temporarily and restore it later - the stack is great for this

We can use MOV Rn,-(SP) to move values onto

the stack... we do it twice with R5 in

this example.

We can then restore it later with MOV (SP)+,Rn...

we also do this twice with R5 |

|

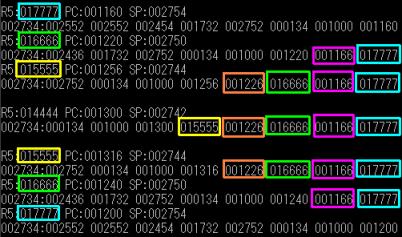

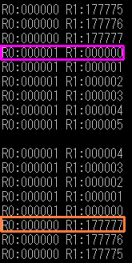

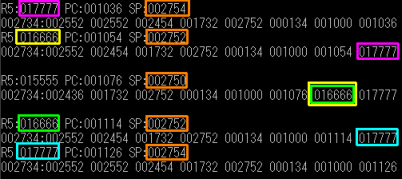

First We pushed 017777 onto the stack

via R5

Next We pushed 016666 onto the stack via

R5

Then we loaded R5 with with 015555

We then restored R5 popping it off the

stack - getting back 16666

We then restored R5 popping it off the stack

- getting back 17777

Notice how SP changes as values

are pushed and popped... SP always points to the Last item pushed

onto the stack |

|

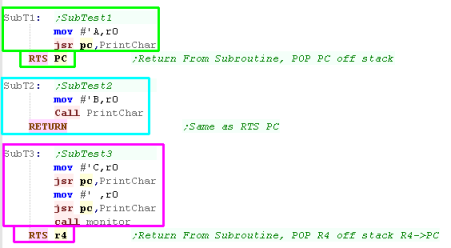

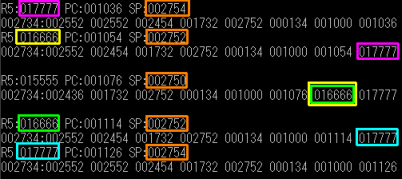

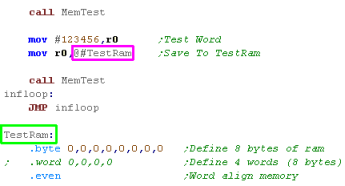

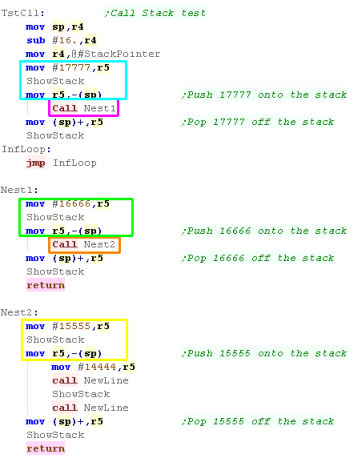

JSR/CALL and the stack

JSR will push a register onto the stack, and move the program

counter into that register...

The CALL command is the same as JSR PC - and is the simplest way

to call a subroutine - whenever we do this the return address will

be pushed onto the stack

in this example we'll push an item onto the stack...

call a sub... push an

item... call a sub and push

a final item,

We'll then pop all the items off the stack and return - in the

reverse order |

|

| The Three Pushes (1,2,3) can be seen on the stack... with the two

Return addresses (1,2)

in between |

|

Because the stack is used by the returning address,

we'll probably want to make sure the stack is in the same position

at the end of the subroutine as it was at the start... so POP off

what you PUSHED on!

If you're super clever you may want to do something tricky with

the stack and calls - but for starters keeping the stack the same

at the end as the start of a sub is best. |

|

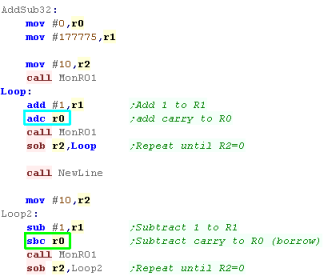

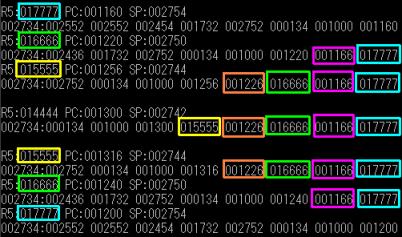

Add and Subtract in

32 bits with ADC and SBC

Just like many other CPU's addition and subtraction that exceeds

the limit of a single register (16 bit on the PDP-11) will affect

the carry flag

When Adding... the carry is effectively any bit that 'overflowed

when the value went over 65536

When Subtracting... the carry is effectively a Borrow, and will be

1 if the calculation went below zero.

To perform 32bit+ addition, first we do the ADD command as normal

for the low word... then we do ADC for the high word

To perform 32bit+ subtraction, first we do the SUB command as

normal for the low word... then we do SBC for the high word |

|

The first example is the ADD/ADC one - when the bottom word (R1)

overflows - ADC adds one to R0

The first example is the SUB/SBC one - when the bottom word (R1)

goes below zero - SBC subtracts0

one from R0

|

|

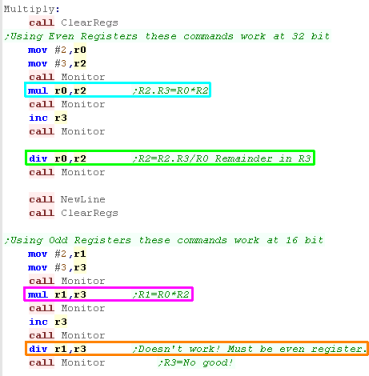

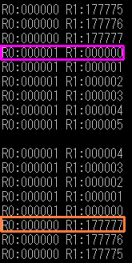

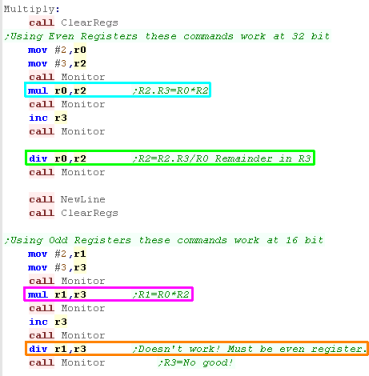

Multiplication and

Division

When we perform a MULtiply command - we can perform an 16 or 32

bit multiplication, this is decided by the number of the

destination register...

If an EVEN numbered register is used with MUL

(like R2) the result will be stored in 32 bit pair (R2,R3)

if an ODD numbered register is used with MUL

(Like R3) the result will be stored as a single 16 bit register

(R3)

DIVide can only work with even registers...

using destination R2 will mean the divided value is in 32 bit pair

(R2,R3) - the integer result will be stored in R2 - the remainder

will be in R3

Using DIVide with an odd pair will not

work (R3 is no good) |

|

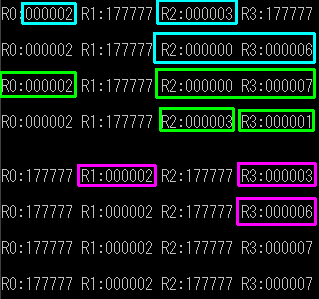

in Example 1 We MULtiplied R0 by R2 and

stored the result in 32bit pair R2,R3

in Example 2 we DIVided 32bit pair

R2,R3 by R0... R2 stored the whole number result... R3 stored the

remained

In Example 3 we MULtiplied R1 by R3, and

stored the result in 16bit register R3

Example 4 did not work - we tried

to use odd register R3 with DIV - this does not work.

|

|

Lesson

5 - Logical and Bit operations

We've looked at some mathematical operations, but we've

really overlooked a lot so far... but we'll catch up now!

Lets take a look at the remaining major commands we'll need!

|

|

|

|

|

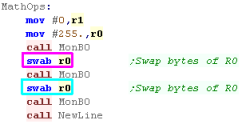

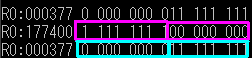

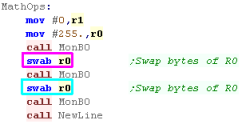

Swap Bytes with SWAB

All our registers are 16 bit - but we can swap the two bytes

within a register with the SWAB command

Here we'll swap the two bytes of R0 with SWAB

then swap them back |

|

| The top and bottom nibbles were swapped -

then swapped back again! |

|

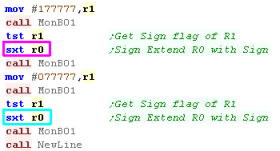

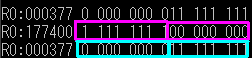

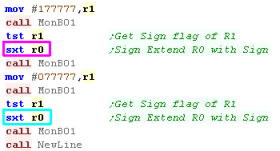

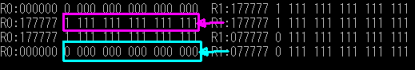

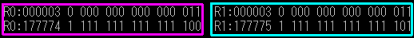

Sign Extending a 16

bit value to 32 bit with SXT

If we want to extend a 16 bit register to a 32 bit register pair

we can do so with SXT...

effectively this command fills a register with the sign bit - so

in this example we update the flags with TST |

|

In the first example SXT extended the 1

sign bit, filling R0 with ones

In the second example SXT extended the 0

bit, filling R0 with zeros |

|

Flipping bits with

COM - Positive to negative with NEG

If we want to flip all the bits in a register, we can do this

with COMpliment...

We may want to convert a positive to negative (or visa versa) we

can do this with NEGate... this effectively

flips all the bits, and adds one |

|

COM flipped all the bits...

NEG flipped all the bits and added 1 (effectively sign

flipping the value) |

|

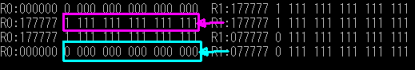

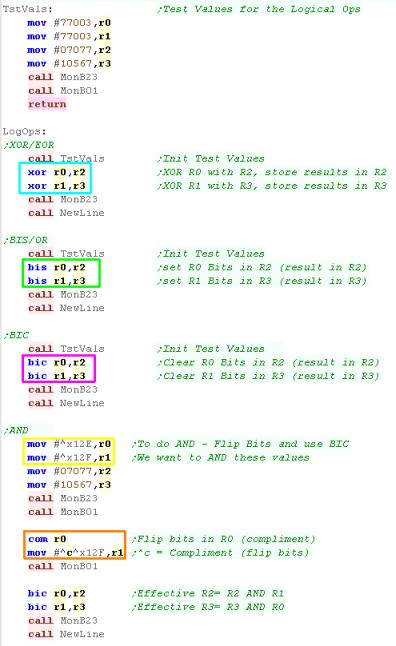

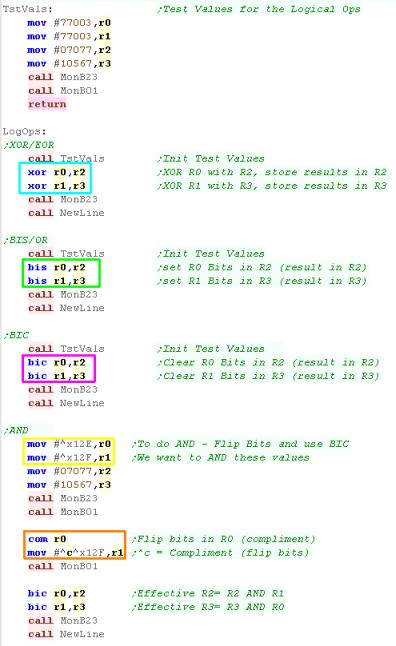

Logical Ops... XOR,

BIS ,BIC

PDP-11 Logical OPS are slightly different

XOR (eXclusive OR) will flip the bits in the

destination when the parameters bits are 1... this is known as EOR

on some CPUS

BIS (BIt Set) will set (1) the bits in the

destination when the parameters bits are 1... this is known as OR

on other CPUs

BIC (BIt Clear) will clear (0) the

bits in the destination when the parameters bits are 1... this is

the opposite of AND on other CPUS

| Operation |

XOR |

BIS |

BIC |

| Destination Reg |

10101010 |

10101010 |

10101010 |

| Parameter Reg |

11110000 |

11110000 |

11110000 |

| Result |

01011010

|

11111010

|

00001010

|

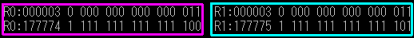

if we want to do an AND we'll

have to be tricky... We need to flip the bits of the value

we want to AND and do a BIC - this will have the same

effect... we can flip the bits with a COM

command... or by getting the assembler to calculate a compliment

with the ^C prefix to a value

|

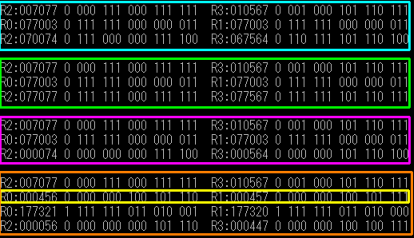

|

| The results of the XOR, BIS,

BIC and fake AND

command can be seen here |

|

|

^C tells the

assembler to calculate the logical compliment (bit flipped)

value... we can chain this with other statements, so ^C^D3 would

complement decimal value 3... ^C^D0F

would compliment Hex value 0F

|

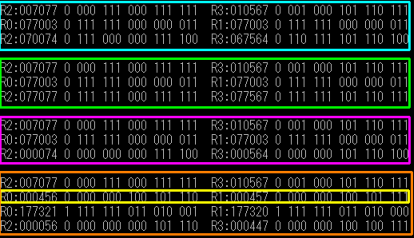

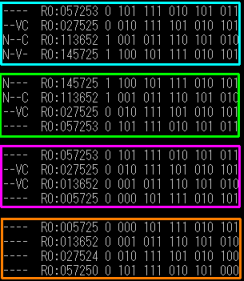

Bit Shifts ROR, ROL,

ASR, ASL

Like most systems, PDP-11 has a range of shifting and rotating

operations

ROR - ROtate Right using carry

ROL - ROtate Left using carry

ASR - Arithmatic Shift Right

ASL - Arithmatic Shift Left

We'll test each command with a loop. |

|

The result of each command can be seen here.

ROR - Bit 0 will be moved to the carry - the

old carry moves to bit 15

ROL - Bit 15 will be moved to the carry -

the old carry moves to bit 0

ASR - Arithmatic Shift Right - new Bit 15

will be the same as last bit 15

ASL - Arithmatic Shift Left - new

Bit 0 will be zero |

|

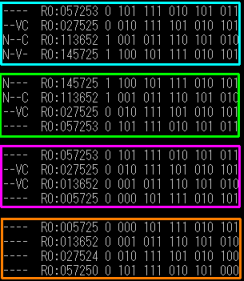

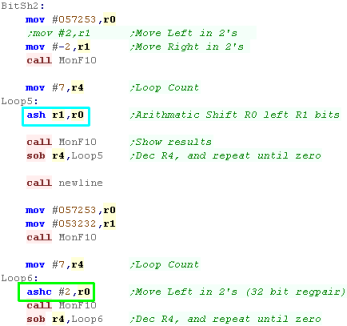

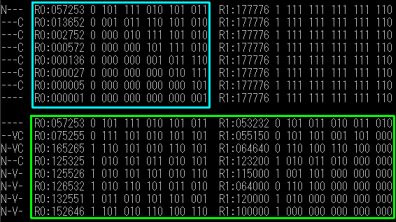

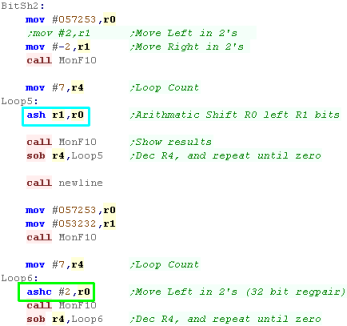

Bit Shifts ASH n

bits... ASHC for 32 bit shifts

If we want to move by more than one bit we can use ASH

A positive shift will shift Left

A negative shift will shift Right

ASH will shift a single register... ASHC will

use a pair of registers (eg R0,R1) as a 32 bit pair |

|

| Here are the results... ASH only affects

one register... ASHC affects the pair of

registers |

|